The Artistic Approach: Bible Studies at the Seminary

by Daniil Kalinov

This year, the “Knowing Christ” students take part in an entirely new weekly class, which is called, simply, “Bible” and is led by Rev. Patrick Kennedy. Below, you can find the reflections about one of the ways of engaging with the Scripture used in this class that can be summarized with the phrase – “an artistic approach”. Also, throughout the text, you can see the artwork the students have created during their long-distance studies in the Fall.

Linden Tree from the Attic

Marc Delannoy

What does it mean to approach something as a creation of art? How do we engage art? To answer these questions, let us imagine ourselves in a gallery. If we look around, we can notice that the design of the room, the lighting, the colors of the walls, the frames – everything is there to emphasize the painting. It all makes the painting the center of attention. Everything draws us to it. Even if we would encounter a mundane object, say a pencil, on a wall, framed like a painting, it would catch our eyes much more than it does in the usual flow of life. So, the first thing that needs to happen for us to engage with artistic creation can be simply called attention. One could say, we first need to grasp an object, register it as a certain unity. Now once this unity is grasped it often starts to work as such on our soul. A reaction, a first feeling-impression, positive or negative, is born in us as we look at the painting. For example, if some of us would actually see a framed pencil in a gallery, they could, at once, feel a certain repulsion: a desire to dismiss this as some sort of “meaningless modern art”. Usually, however, in our journey through the gallery, we do find a painting that we like. We want to stop and let that impression linger in our soul. At this point, we can feel quite satisfied with simply enjoying the effect the painting has on us. But, after a time, we can start to go deeper into its details. We stop at the individual forms, elements of composition, particular colors, different characters, and so on. Through this, we gradually start to be interested in the painting itself and not only in the feeling it produces in us. We start to contemplate the art-piece instead of simply enjoying it. This process, when we are really interested in the art object, can transform into a full-fledged study. Every historical detail about it, every sentence the author itself and other people said about it, can become dear to us. We try to see and understand every part of the painting, which we first approached as a unity, and try to draw connections between them. In this process we can sense that the initial impression that the painting had on us is slowly being extinguished; however, we also feel that the warmth of our honest selfless interest is helping to bring into being a newer, fuller, much more objective appreciation of it instead. Before we could only say that we like the painting, now we could talk about it for hours. We know every little aspect of it, can picture it lively before our mind's eye, maybe even draw it ourselves if we have the skill. All the inner lawfulnesses that stand behind the painting now live within us. We stop being mere spectators. Instead, we actively participate in that, which brought this art object into being. Ultimately, by approaching something as art, we ourselves become artists.

But what about all other “mundane” things which we neither see in galleries, encounter on the pages of poetry books nor hear in the concert halls? How are they different? For sure, confronted with human artistic work it is easier for us to trust that there is another, deeper layer to reach. We know that the artist, especially if he is a master, tried to express in his work something, which he had in his mind beforehand. But we can also be aware that with the natural objects too, the whole thing is not given to us if we simply stare at them. Could we gain something by approaching them in the same way we approach art? Well, one can at least try and see what happens.

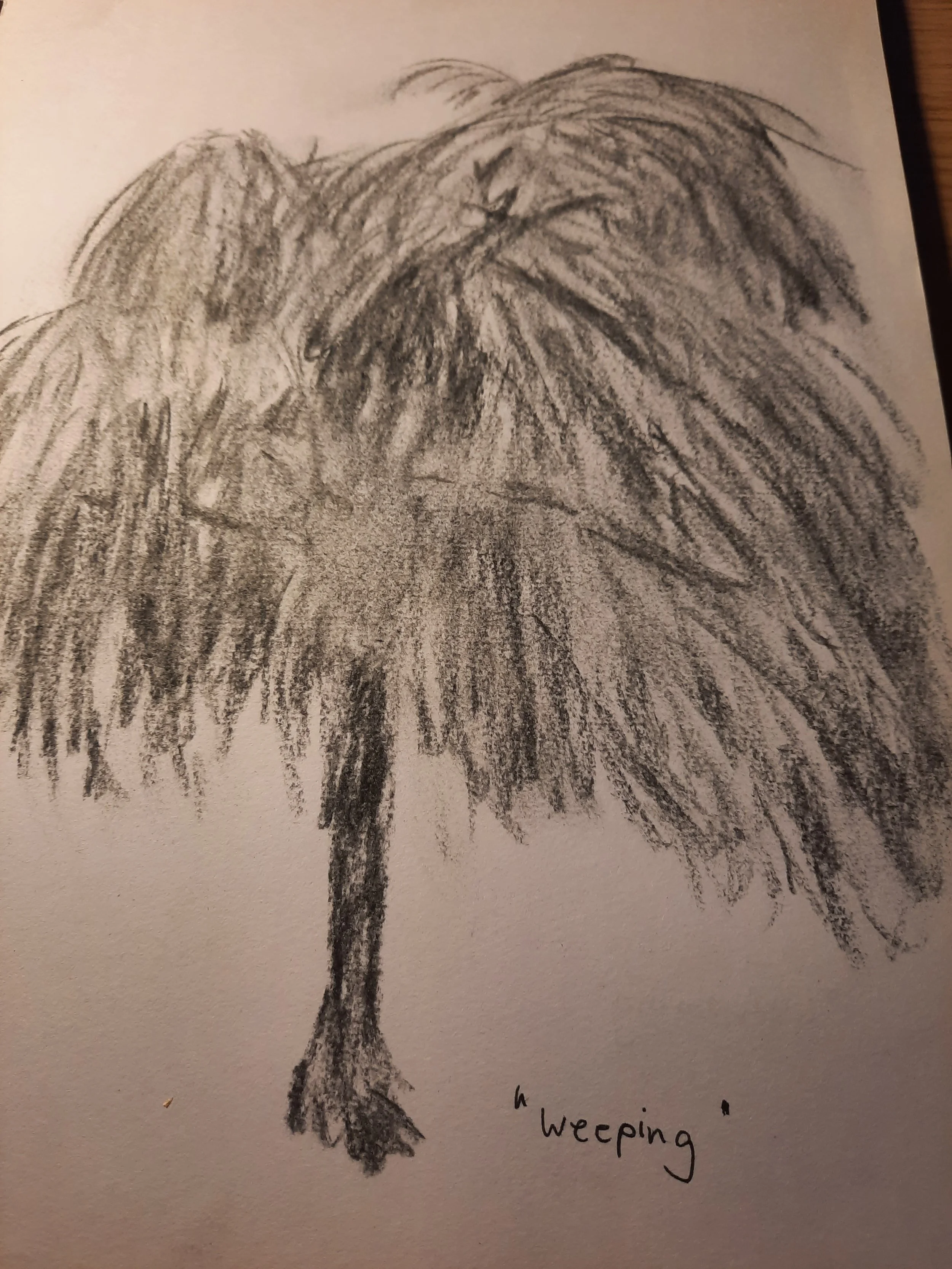

Such an attempt was in fact the part of the long-distance part of our (‘Knowing Christ’ students) studies in the fall. We all chose a tree in our immediate neighborhood. The next few months we were to live with this tree as an art-piece. We observed it, drew or painted it, observed it once more, saw all the things we didn’t see before, painted it again, and so on. And we could all feel that our relationship to the tree did change. It became much more alive for us. We started to feel something of the story, the gesture and the basic mood of our tree. And it is this inner reality of the tree, which we allowed more and more to guide our work. Until we could also express it in a totally different medium of our words and concepts, as we finished our work by writing short poems about it.

Weeping Willow

Silke Chatfield

Silver Maple

Claudia Pfiffner

However, this work was also to prepare us for something else. It was to help us develop the skill required for this kind of artistic engagement. The skill, which here in the Seminary, we could apply to the text central for all of our studies: the Bible.

Is it such a strange idea to approach Scripture – in addition to all other ways one could approach it – also as art? It does, after all, have a form of a literary creation: of a collection of stories, poems, songs and letters. But (as Robert Alter also points out in the Introduction to his translation of the Hebrew Bible) it seems that many a person in our culture can hesitate to do so, for one or another reason. Some of us may feel that it is irreverent to approach it as we approach human creations; isn’t it the Word of God? Or we might feel that the most obvious literal layer of the text is already the whole truth; are we some kind of Gnostics to seek for hidden truths? We may also sense that there is a danger in analyzing the text too much; the modern theologians did so, and for many the text crumbled in their hands. The naive understanding of the text disappeared, but there was no other to be found.

But if we take seriously what the Bible is and what it says about itself, this is the path we should actually take. Indeed, as far as its physical manifestation is concerned it is just a book, a literary work, a story. It is not the Word of God. But the spirit, who lives and breathes through it, is. It is the Creative Word, the Logos, the Christ. And it is He, as the story of two disciples on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24) tells us, who can open the inner meaning of the Scripture to us. But it also requires some work on our part. We need to engage the text, analyze it, selflessly give ourselves to all the little details of it. And if we do so in His warm Presence, we can be sure that the text will not crumble, but receive newer and fuller life.

We, the seminary students, can confess to that. The last few weeks, Rev. Patrick Kennedy was leading us in the careful and slow study of the first 4 chapters of Genesis, concentrating mainly on the first one. And we could see how just looking at the language, the unique turns and twists of the narrative on its overall composition can shed so much light on this story. Suddenly instead of an old well-known and a well-worn tale we were in the beautiful living world of meaning, insight and interconnections.

Tree

Daniil Kalinov

Our Author:

Daniil Kalinov is a student in the “Knowing Christ” program and a Greek Teacher at the Seminary.

He has also spent this fall in the Sister-Seminary in Stuttgart.

This is a blog entry by a student at The Seminary of the Christian Community in North America. These are posted weekly by the student editorial team of Marc Delannoy and Silke Chatfield. For more information about our seminary, see the website: www.christiancommunityseminary.ca and for even more weekly podcast and video content check out the Seminary’s Patreon page: www.patreon.com/ccseminary/posts.

The views expressed in this blog entry do not necessarily represent the views of the Seminary, its directors or the Christian Community. They are the sole responsibility of its author.